A central question in contemporary ethics and political philosophy concerns which entities have moral status. Footnote 1 Any specific view on this issue has far reaching implications. Having moral status makes all the difference for an entity—it changes how it ought to be treated, what it is entitled to, and what legal, political, social, and economic institutions should be realised to respect it. Footnote 2

In this article, I provide a detailed analysis of the view that moral status comes in degrees. Such an analysis is important for at least two reasons. The first reason concerns our understanding of the concept of moral status. Though this is not the first article to discuss the idea that moral status admits of degrees, this topic remains relatively undertheorized in the literature. Footnote 3 I argue that degrees of moral status can be specified along two dimensions: i) the weight of the reason to protect an entity’s morally significant rights and interests; and/or (ii) the rights and interests that are considered morally significant. Footnote 4 One upshot of my analysis is that having more morally significant rights and interests often signals having higher moral status. But this is by no means necessary. Instead, entities with more morally significant rights and interests may have lower moral status than entities with fewer rights and interests.

Another upshot of my analysis is that entities can have radically different morally significant rights and interests, yet still have equal moral status. This relates to the second reason for examining what it means to say that moral status comes in degrees: the attribution of moral status to nonparadigmatic entities. Paradigmatic adult human beings have, for better or worse, become paradigmatic examples of entities with (full) moral status. But the concept of moral status also plays an important role in relation to other entities, such as people with severe cognitive disabilities, children, embryos and foetuses, dead human beings, aliens (of various sorts), robots, non-human animals, non-conscious living organisms, ecosystems, plants, rivers, and works of art. Footnote 5 However, we may ask what moral status could be if it can be had by such different entities; and we might reasonably doubt if they (or some of them) can be grouped together under a normatively significant kind.

To bring clarity to this issue, we need an account of what it means to say that moral status comes in degrees. In light of that, my aim is conceptual rather than justificatory. Specifying the most plausible account of moral status is a topic for another occasion. I focus on how that account, whatever it ends up being, could be most accurately described and distinguished from its alternatives.

The structure of this article is as follows. In Section 2, I make some preliminary remarks about my analysis of moral status. In Section 3, I discuss the idea that entities can have ‘higher’ or ‘lower’ moral status. In Section 4, I argue that degrees of moral status can denote (i) differences in the weight of the reason to protect an entity’s morally significant rights and interests and/or (ii) differences in the rights and interests that are considered morally significant. In Section 5, I discuss how these two dimensions could be combined and which implications this has for the idea that moral status admits of degrees. In Section 6, I summarize my analysis.

I will make two preliminary remarks about my analysis of moral status. The first remark concerns the ground of moral status. The second remark concerns the bundle of rights and interests that come with having moral status.

First, I will say that the moral status of an entity is grounded in the fact that it possesses a status property. Footnote 6 Examples of such a status property are sentience, cognitively sophisticated capacities, or membership of some group (e.g. ‘mankind’). Footnote 7 To illustrate, if entities have moral status if and because they are sentient, sentience is a status property. Moreover, I will say that entities ‘possess’ a status property. This could mean that they have that property, that they display or exhibit that property, that they can develop that property, and so forth. My analysis is compatible with these and other specifications of ‘possessing a status property’.

It is worth examining the idea of a status property in more detail. Some philosophers defend an atomic status property. If the status property is atomic, the fact that an entity possesses a property which, at least on the face of it, is neither conjunctive nor disjunctive, grounds an entity’s moral status. Agnieszka Jaworska, for example, argues that “the emotional capacity to care” Footnote 8 is a sufficient condition for moral status, and this capacity to care is atomic in the sense I intend here. Subsequently, complex status properties are status properties recursively formed from atomic properties via disjunction (property P or property Q) or conjunction (property P and property Q). By using the concept of atomic properties and disjunction and conjunction, we can define potential status properties.

Disjunctive status properties can play an important role when considering the moral status of nonparadigmatic entities. Consider the question of what, if anything, can ground the moral status of rivers. Footnote 9 Suppose that having cognitively sophisticated capacities is a status property. Because rivers lack cognitively sophisticated capacities, we must look for alternative status properties or reject the idea that rivers can have moral status. Robert Elliot argues that naturalness, which is “the property of being naturally developed” Footnote 10 , can be the basis of moral value. And so, the moral status of an entity might be grounded in the fact that it possesses the disjunctive status property P1 (cognitively sophisticated capacities) or (naturalness)]. This would mean that both entities with cognitively sophisticated capacities and natural entities, such as rivers, have moral status. Alternatively, the moral status of rivers might be grounded upon facts attributed to them by indigenous communities. For example, the status property could be P2 [(cognitively sophisticated capacities) or (naturalness and being embedded in indigenous tradition)]. This view holds that both entities with cognitively sophisticated capacities and some rivers have moral status, even if they do not share any atomic property. And it would explain why only certain rivers have moral status (e.g. indigenous communities may attribute the relevant properties to some but not all rivers). To be sure, nothing I will say about the concept of moral status requires that one endorses such a disjunctive status property. But I consider it to be a valuable starting point for theorizing about the moral status of nonparadigmatic entities.

Second, I will say that if entities have moral status, they have a bundle of rights (e.g. a right against interference) and/or interests (e.g. an interest in avoiding pain). Footnote 11 These rights and interests are morally significant, which means that we have normative reasons to protect them. And generally speaking, the higher the moral status of an entity, the greater the weight of the reason to protect its bundle of rights and interests (see Section 4.1).

However, someone might object that moral status comes with more than a bundle of rights and interests. Or perhaps that moral status comes with something else than such a bundle. For example, perhaps moral status (also) comes with duties and responsibilities, authority or other deontic incidents, moral worth or considerability, or some other kind of value. I will leave this aside for the purpose of this article. Instead, whenever I say ‘bundle of rights and interests’ or some cognate of that term, one might add (or omit) from this bundle whatever one believes needs adding (or omitting). For my particular purpose, nothing important depends on this.

I will propose a novel framework for understanding the idea that moral status admits of degrees. This framework refines a common typology of this idea and it sheds new light on what it means to say that moral status is a ‘range property’.

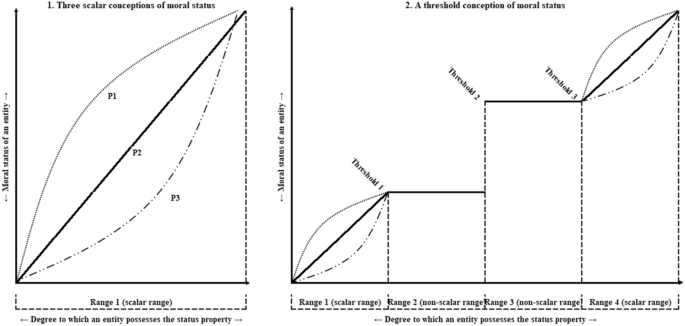

There are two general ways of understanding the idea that moral status admits of degrees. Footnote 12 According to scalar conceptions of moral status, there is a continuity in degree to which entities possess the status property and their moral status. Footnote 13 The higher the degree to which they possess the status property, the higher their moral status. And the lower the degree to which they possess the status property, the lower their moral status. Alternatively, according to threshold conceptions of moral status, there is a discontinuity, demarcated by a threshold, in the degree to which entities possess the status property and their moral status. Footnote 14 This threshold marks a morally significant shift in moral status. Some threshold conceptions posit a single threshold, whereas others posit two or even more thresholds, each of which denotes a morally significant shift in moral status. Footnote 15

This typology of the idea that moral status admits of degrees suffices for some purposes. It distinguishes two broad categories of views about the idea that moral status admits of degrees and it indicates some of their main challenges. For threshold conceptions, for example, it raises the challenge of justifying a discontinuity in the degree to which entities possess the status property and their moral status. And for scalar conceptions of moral status, it raises the question if differences in moral status are only gradual or if they can also be more fundamental.

However, we can bring more conceptual clarity and versatility to the idea that moral status admits of degrees by unifying scalar conceptions and threshold conceptions under a single conception of moral status. Any view about moral status as admitting of degrees can be captured by drawing on two distinctions. The first distinction is between a continuum and a range of degrees to which entities can possess the status property. A continuum encompasses all degrees to which entities can possess the status property. This could be either a continuous quantity or a discrete quantity. Higher degrees on the continuum mean that entities possess the status property to a higher degree. And lower degrees on that continuum mean that they possess the status property to a lower degree. Subsequently, ranges are subsets of consecutive degrees to which entities can possess the status property. A range may contain all degrees on the continuum or only some of them. If there is more than one range on a continuum, these ranges are demarcated by thresholds. And if there is a single range on a continuum, that range encompasses the entire continuum.

The second distinction is between scaler ranges and non-scalar ranges. In scalar ranges, entities have different degrees of moral status if they possess the status property to a different degree. Footnote 16 And they have equal moral status if they possess the status property to an equal degree. Subsequently, in non-scalar ranges, all entities have equal moral status even if they possess the status property to different degrees.

We can now refine the common typology of the idea that moral status admits of degrees. Threshold conceptions of moral status maintain that entities in the range above the threshold have higher moral status than those in the range below the threshold. Moreover, the ranges demarcated by the threshold can be scalar ranges or non-scalar ranges, meaning that within these ranges entities can, in principle, have different degrees of moral status or not. Accounts of moral status with multiple thresholds posit not two but more ranges, each of which are scalar or non-scalar. Subsequently, according to scalar conceptions of moral status, there is no threshold at which a morally significant shift in moral status occurs. Footnote 17 Instead, there is a single range and entities have different degrees of moral status if they possess the status property to a different degree. That is, scalar conceptions hold that there is a single range on the continuum and that this range is a scalar range.

To illustrate, consider the views in Figure 1. The first view is a scalar conception of moral status. It shows three possible specifications of degrees to which entities can possess the status property and degrees of moral status (P1, P2, and P3). The second view is a threshold conception of moral status with multiple thresholds (Threshold 1, Threshold 2, and Threshold 3). These thresholds demarcate ranges of degrees in which entities can possess the status property. Ranges 1 and 4 are scalar ranges, in which the moral status of an entity increases or decreases with the degree to which it possesses the status property. Ranges 2 and 3 are non-scalar ranges, which means that all entities have equal moral status. I am not aware of anyone defending this particular view, but it shows how scalar and non-scalar ranges can be combined. Footnote 18

I will now turn to what it means (and what it does not mean) to say that moral status is a range property, which is something advocates of threshold conceptions of moral status often defend. Footnote 19 I take the following characterization of this idea to be the standard interpretation. If moral status is a range property, there is a relationship between two properties, such as the property ‘having moral status’ and the status property (e.g. sentience or sophisticated cognitive capacities). Footnote 20 The property ‘having moral status’ is a binary property, which means that entities either lack moral status or have moral status (similarly, the property 'having an n-tier of moral status’ is a binary property). But the status property itself is a scalar property, meaning that entities can possess the status property to different degrees. Consequently, if moral status is a range property, the property ‘having moral status’ is a range property with respect to the status property if certain degrees to which entities possess the status property mean that they have the property ‘having moral status’ whereas other degrees mean that they lack that property.

This characterization of range properties may suffice in some cases. But the above framework can more precisely characterize what saying that moral status is a range property entails: if moral status is a range property, there is a non-scalar range on the continuum. More precisely, there is at least one range in which differences in the degree to which entities possess the status property entail neither differences in the weight of the reason to protect an entity’s bundle of rights and interests nor differences in the bundle of rights and interests. However, if moral status is a range property, this does not imply that all entities that possess the range property are therefore in the highest range. This putative implication of moral status as a range property is widely assumed, for example in the idea that entities in the highest range have equal and full moral status. Footnote 21 But range properties need not denote the highest range, as Ranges 2 and 3 in Fig. 1 show. Footnote 22

This is an important insight when attributing moral status to nonparadigmatic entities. Consider again the case of rivers. We need not say that the moral status of rivers, or of other parts of nature, increases or decreases with the degree to which they possess the status property. Instead, rivers might have lower moral status than paradigmatic human beings, yet have equal moral status to other rivers (or other parts of nature) because in their tier of moral status, moral status is a range property (for example, equal moral status applies even if, say, some rivers are more 'natural' than others). Among other things, this has important epistemic advantages. For example, Clare Palmer argues that it may be unclear what protecting the rights and interests of certain nonparadigmatic entities entails. Footnote 23 It may be difficult to establish what is in the interest of ecosystems or species (e.g. is it in the interest of a species to speciate?). And if so, it is difficult to know how such nonparadigmatic entities should be treated even if they are attributed moral status. But the strength of this objection depends, at least in part, on how fine-grained we understand the moral status of such entities and the differences in moral status between them.

Finally, I argue below that there may be ranges in which there is a difference in the weight of the reason to protect an entity’s bundle but not in the size and content of the bundle itself; or differences between bundles but not in the weight of the reason to protect these bundles. This does not fall under the common understanding of the idea of a range property, even though it means that there is a property that is shared among all entities in a specific range (e.g. a specific weight that attaches to the reason to protect their bundle or a bundle of a specific size).

I have discussed the relationship between the degree to which entities possess the status property and their degree of moral status. But an account of moral status must also say which normative commitments correspond with degrees of moral status. I will argue that this can be specified along two different dimensions, namely (i) the weight of the reason to protect an entity’s morally significant rights and interests (Section 4.1) and/or (ii) the rights and interests that are considered morally significant (Section 4.2). Footnote 24 I discuss these normative commitments in turn.

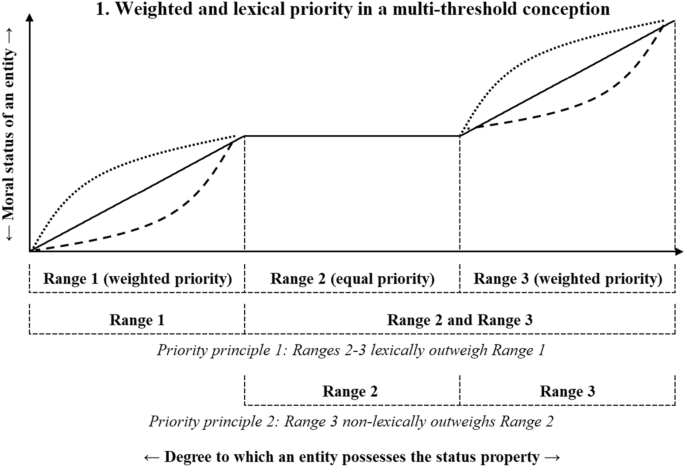

Degrees of moral status can denote differences in the weight of the reason to protect an entity’s bundle. If so, the higher the moral status of an entity, the weightier the reason to protect its bundle. And the lower the moral status of an entity, the less weighty the reason to protect its bundle. I first examine three ways in which the weight of the reason to protect an entity’s bundle can differ depending on its degree of moral status. I then propose a novel response to the objection that certain degrees of moral status cannot always have priority over other degrees of moral status. I end by discussing how priority can be given to specific rights and interests within bundles rather than to specific bundles in general.

Reason R+ to protect the bundle of an entity with higher moral status can outweigh reason R- to protect the bundle of an entity with lower moral status in three different ways. First, R+ might always outweigh R-. In that case, R+ ‘trumps’ or ‘lexically outweighs’ R-. Second, R+ might outweigh R- all else being equal but not necessarily, in which case R+ has ‘non-lexical priority’ (or ‘weighted priority’) over R-. This allows for the possibility that in some cases R- outweighs R+. If we assume a non-lexical weighing principle rather than a lexical weighing principle, a minor harm to an adult human being may be justified if doing so prevents a major harm to a mouse, even if adult humans have higher moral status than mice. Third, R+ can silence or disable R-. We can refer to this as exclusionary priority. Footnote 25 For example, perhaps the rights and interests of entities with high moral status cannot be overridden for the greater good, whereas the rights and interests of entities with lower moral status can be overridden for the greater good. Unlike in the case of lexical or non-lexical priority, here the point is not so much that reasons are outweighed but that they are disabled in the context.

To see how these three ways of giving priority relate to the idea that moral status admits of degrees, recall that a range is a subset of consecutive degrees to which entities can possess the status property. First, the weight of the reason to protect an entity’s bundle must be specified between ranges. The reason to protect the bundle of entities in higher ranges has more weight than the reason to protect the bundle of entities in lower ranges, which means that the former reason lexically, non-lexically, or exclusionary outweighs the reason to protect the bundle of entities in a lower range. Second, the weight of the reason to protect a bundle must also de specified within ranges. In non-scalar ranges, the reasons to protect a bundle always have equal weight. But in scalar ranges, the reason to protect a bundle has more weight the higher the degree to which entities possess the status property.

To illustrate, consider the view in Figure 2. It holds that within Range 1 and within Range 3, the higher an entity’s moral status, the more non-lexical weight attaches to the reason to protect its bundle. And within Range 2, the reasons to protect bundles of different entities have equal weight because all entities in that range have equal moral status. Subsequently, it also specifies priority principles between ranges. The reason to protect the bundles of entities in Range 2 and Range 3 lexically outweighs the reason to protect the bundle of entities in Range 1. But when considering bundles of entities in Range 2 and Range 3, no lexical priority is given and non-lexical priority is applied instead. As a result, the reason to protect the bundle of an entity in Range 3 typically but not always outweighs the reason to protect the bundle of an entity in Range 2.

We can now turn to a common objection to giving lexical priority to the reason to protect certain bundles over others. This objection is that lexical priority puts too much moral weight on a specific threshold. For example, Rainer Ebert argues that minor changes in the possession of the status property cannot explain major shifts in the reason to protect a bundle. Footnote 26 I agree that such a major shift is difficult to justify. However, lexical priority need not come with major shifts, namely if only large enough differences in degrees of moral status can justify lexically prioritizing certain bundles over other bundles.

Consider a view with three ranges. Suppose it holds that we must non-lexically weigh the reasons to protect the bundle of entities between either the lowest range and the middle range or the middle range and the highest range. However, this is compatible with saying that the reason to protect the bundle of an entity in the highest range lexically outweighs the reason to protect the bundle of an entity in the lowest range. If (and only if) we consider cases in which protecting the bundle of entities in the highest range conflicts with protecting the bundle of entities in the lowest range, we must apply lexical priority. Here, a minor change in the possession of the status property does not result in a major shift in the reason to protect a bundle. Yet, this view does maintain a distinctive commitment to lexically prioritizing the reason to protect the bundle of certain entities over the bundle of other entities.

Finally, so far, I have only considered bundles as such rather than the specific rights and interests which make up such bundles. For instance, I have said that if Range 2 has lexical priority over Range 1, the reason to protect the bundle of an entity in Range 2 always outweighs the reason to protect the bundle of an entity in Range 1. However, accounts of moral status can qualify this claim and say that lexical priority (or some other form of priority) only applies to the reason to protect specific elements of a bundle. For example, they might say that only the rights but not the interests in the bundle of an entity in the range above the threshold lexically outweigh the interests in the bundle of the entity in the range below the threshold. And similar arguments can be made for differences between specific interests or between specific rights. To return to the example of rivers and parts of nature as potential bearers of moral status, one might hold that a minor harm to an adult human being might be justified if that avoids a major damage to a river. Yet this is compatible with saying that if the choice is between killing a human being or protecting the river, the reason to protect the human being’s right not to be killed lexically outweighs the interests of the river. Hence, some but not all elements of a bundle of rights and interests of entities with higher moral status may have lexical priority (or some other form of priority) over the rights and interests of entities with lower moral status.

Degrees of moral status can also denote differences in the bundle of morally significant rights and interests. For example, entities with the highest degree of moral status may have a moral right against interference whereas other entities have no such right. Footnote 27 Moreover, it is sometimes said that only entities with full moral status have rights, whereas concerns for nonparadigmatic entities typically take the form of concerns with their interests. Footnote 28 I will distinguish two dimensions along which the bundles of entities can differ. I then discuss how these differences relate to the idea that moral status admits of degrees.

Bundles of rights and interests can differ in two ways. First, quantitative differences are differences in the cardinality of bundles. For example, if bundle B1 contains five rights and interests and bundle B2 contains six rights and interests, there is a quantitative difference between these bundles. Footnote 29 Second, qualitative differences are differences in the content of the bundle. There is a qualitative difference between bundles B1 and B2 if B1 contains at least one right or interest that is not part of B2 (or the other way around).

This distinction between quantitative and qualitative differences between bundles might seem unnecessary. First, quantitative differences require qualitative differences. Entity E1 can only have more rights and interests than entity E2 if E1 has a right or interest that E2 lacks. And so, quantitative differences assume qualitative differences. This might suggest that we need not distinguish between quantitative and qualitative differences between bundles. Second, quantitative differences might seem to correspond with degrees of moral status. Larger bundles suggest higher degrees of moral status; smaller bundles suggest lower degrees of moral status. But it is not evident that qualitative differences also correspond with degrees of moral status. And so, one might question the relevance of qualitative differences between bundles for the purpose of understanding what it means to say that moral status admits of degrees.

However, the distinction between quantitative differences and qualitative differences between bundles is important, especially when considering the moral status of nonparadigmatic entities. Consider this example from the recent philosophical literature. Some scholars recognize the possibility that entities with seemingly equal moral status may have different bundles. Thomas Douglas, for example, says that entities with equal moral status can have different rights or claims:

[T]wo beings with the same moral status may have different rights or claims because of their different internal or external circumstances. For example, a more severely injured person may have a stronger claim to medical assistance than a less severely injured one even though they share the same moral status. Or one mildly injured person may have a stronger claim to medical assistance than a moral equal because her medical assistance can be provided at lower cost. Footnote 30

According to Douglas, entities with equal moral status have stronger and weaker claims to medical assistance depending how badly they need it and how costly such assistance would be. However, I doubt this shows that these entities have fundamentally different rights (or interests). Rather, they seem to have an equal right to adequate medical assistance, where ‘adequacy’ is a function of the severity of the injury and the costs associated with providing assistance. In other words, they have an equal right to adequate medical assistance even though they do not have an equal actual claim to medical assistance. Hence, this does not show that entities with the same moral status may have different rights. However, it does raise the question if there can be more radical differences between bundles of entities with equal moral status.

I hesitate to say that the following examples are accurate (I am not sure about this and accounts of moral status will differ in their assessment of it), but they serve the purpose of illustrating what I am after. An account of moral status might say that there is a difference between the bundle of children and that of adult human beings. It can make a moderate claim or a radical claim about this difference. The moderate claim is that adult human beings have all the rights and interests of children and at least one additional right or interest; or that children have all the rights and interests of adult human beings and at least one additional right or interest. This moderate claim is a claim about a quantitative difference between their respective bundles. Subsequently, the radical claim is that the bundle of adult human beings lacks at least one right or interest that is part of a child’s bundle and that the bundle of children lacks at least one right or interest that is part of the adult human being’s bundle. Perhaps only children have, following Anca Gheaus’ work on the value of childhood, a right to “unstructured time for play and exploration, chances to exercise their fantasy and the protections needed not to worry about their future” Footnote 31 . And perhaps only adult human beings have a right to self-determination. The radical claim has a distinctive qualitative element, namely that children and adult human beings have interests and/or rights that are not shared between them.

There may be other examples of radically different bundles, especially if we consider other nonparadigmatic entities. For example, if both human beings and rivers have moral status, this does not imply that they have similar rights and interests. It may be difficult to establish which rights or interests are morally significant in the case of rivers. Yet it seems that whatever they are, they will differ at least in part from the rights and interests of human beings. For example, what is required to benefit a river may differ from what is required to benefit a human being. Hence, the rights and interests of rivers need not be also rights and interests of human beings (or the other way around). If the radical claim about the bundle of adult human beings and children holds, or if a similar radical claim is true for other types of entities (e.g. rivers, animal species, robots, etc.), this shows that bundles can differ both along a quantitative and a qualitative dimension.

This brings us to the relation between differences between bundles and degrees of moral status. In my view, quantitative differences between bundles do not imply different degrees of moral status. Suppose two entities have different morally significant rights even though the size of their respective bundles is equal. It does not necessarily follow that they have equal moral status. But neither does it follow that they have unequal moral status. And so, the content of the bundle by itself does not determine the moral status of an entity. Moreover, it is not evident that any larger bundle of rights and interests is necessarily tied to a higher degree of moral status than any smaller bundle of rights and interests. We should at least be open for the possibility that this is not the case. Smaller bundles might contain rights or interests that merit significantly more protection than larger bundles with other rights and interests.

That does not mean that we cannot say anything about the relation between quantitative and qualitative differences between bundles and degrees of moral status. But it does mean that, at an abstract level, there may not be much we can say about this with great confidence. Generally speaking, qualitative changes in an entity’s bundle of rights and interests seem more naturally combined with a discontinuity in degree to which entities possess the status property and their moral status, rather than with a continuity in the degree to which entities possess the status property and their moral status (e.g. perhaps only entities above the threshold have morally significant rights). Moreover, it seems plausible that there is a tendency for larger bundles to correspond with higher degrees of moral status. However, as I have argued in the discussion about the bundles of children, adult human beings, and rivers, neither qualitative nor quantitative differences between bundles are necessarily tied to higher or lower degrees of moral status. If an account of moral status aims to attribute (or leave open the possibility of attributing) moral status to these and other nonparadigmatic entities, the relationship between the content and size of a bundle and the degree of moral status of the holder of that bundle can be difficult to specify, both in theory and in practice.

I have argued that degrees of moral status can be specified along two dimensions: (i) the weight of the reason to protect an entity’s bundle (or specific rights or interests in that bundle); and/or (ii) the specific rights and interests that are considered morally significant. Accounts of moral status often combine these normative commitments. For example, a threshold account might motivate a shift in the weight of the reason to protect a bundle by saying that only entities above that threshold have rights and that such rights merit distinctive protection. In what follows, I will explore how accounts of moral status link degrees of moral status to the weight of reasons to protect bundles and/or the content and size of these bundles.

Looking at the contemporary literature on moral status, we can point out some current trends in light of the analysis in this article. Given the practical focus of the early literature on moral status, which tried to establish that animals have moral status in an attempt to criticize their atrocious treatment, there has been much interest in views which establish that the moral status of at least some animals merits strong protection. Such views often endorse a non-lexical priority view of the weight of the reasons to protect their bundle. Footnote 32 And they typically endorse a threshold conception of moral status where thresholds indicate both additional rights or interests that merit protection, and that the reasons to protect these bundles have more weight. Subsequently, theorists who ground moral status on sentience or other scaler status properties typically reject threshold conceptions of moral status in favour of scalar conceptions. Among other things, this sets such views apart from views that consider certain entities to be paradigmatic holders of full moral status (e.g. paradigmatic adult human beings). And third, there has been a growing interests in moral status and nonparadigmatic entities. Earlier I mentioned the example of people with severe cognitive disabilities, children, embryos and foetuses, dead human beings, aliens, robots, non-human animals, non-conscious living organisms, ecosystems, plants, rivers, and works of art. At least for some of these entities it seems clear that if they can be attributed moral status, it must be grounded upon different properties than in the case of paradigmatic holders of moral status. In light of this, some theorists focus on pluralism regarding status properties. Footnote 33

Moreover, the analysis of moral status in this article has some other important implications for theorizing about moral status. If degrees of moral status denote differences along two dimensions, we may be unable to offer a transitive ranking of the moral status of different entities. For example, the moral status of entity E1 might be higher than the moral status in entity E2 in the sense that the size of E1’s bundle is larger than the size of E2’s bundle. Yet the moral status of E2 might be higher than the moral status of E1 in the sense that the reason to protect E2’s bundle has more weight than the reason to protect E1’s bundle. If an account of moral status must offer a transitive ranking, it needs to offer a solution to issues, either by arguing that such cases are conceptually impossible or that they do not occur in practice.

Let me consider some further issues that arise when combining the two normative commitments that might correspond with degrees of moral status. The first is that ranges on a continuum can be non-scalar ranges in one dimension but scalar ranges in another dimension. Consider an account of moral status with one threshold. Suppose it holds that entities in the range below the threshold have the same bundle of normatively significant interests even if they possess the status property to different degrees. But the higher the degree of moral status of an entity, the more weight attaches to the reason to protect its bundle. Hence, this range below the threshold is both a scalar range and a non-scalar range. It is scalar because the weight of the reason to protect the bundles of entities in that range increases and decreases depending on the extent to which they possess the status property. Yet it is also non-scalar because the bundle of rights and interests is the same for all entities in that range. Such a view might, moreover, hold that in the range above the threshold, all entities have equal bundles and no priority is given. And so, that range is non-scalar both regarding the weight of the reason to protect a bundle as well as the size and content of bundles.

Subsequently, the normative commitments that correspond with degrees of moral status can also be combined in more complex ways. Let me discuss three of them. First, entities whose bundle of rights and interests merit equal protection may have different bundles. Recall the example of children and adult human beings. One might say that the reason to protect the bundle of children has the same moral weight as the reason to protect the bundle of adult human beings. Under this assumption, there is no difference between children and adults in terms of the weight of the reason to protect their respective bundles. Yet this is compatible with claims about both quantitative and qualitative differences in their respective bundles. Similarly, even if human beings and rivers have different bundles, the reasons to protect their bundles may have equal weight. What this means, then, is that different bundles might merit equal protection.

Second, among entities with equal bundles, unequal weight might be attached to the reasons to protect their respective bundles. For example, both mice and children may share an interest in not being physically harmed. But for children this interest may have more weight than for mice if children have higher moral status than mice. If so, degrees of moral status need not denote different interests but different weight that is given to these interests. Importantly, this difference cannot be explained by the fact that children enjoy a more extensive bundle of rights and interests than mice. This is because enjoying a more extensive bundle of rights and interests does not imply that one’s rights and interests should therefore have more weight. The weight of the reason to protect a bundle and the size of that bundle are different types of normative commitments that may but need not coincide.

Third, the demarcation of specific ranges on the continuum may vary depending on whether we consider the weight of the reason to protect a bundle or the size and content of that bundle. For example, perhaps on the same continuum there is one shift in the size and content of a bundle whereas there are two shifts in the kind of priority that is assigned to protecting specific bundles. Such a view posits two ranges with regards to differences in the size and content of bundles, whereas it posits three ranges with regards to the weight that is given to protecting specific bundles. This means that on a single continuum of degrees to which entities can possess the status property, there can be ranges which denote the weight of the reason to protect an entity’s bundle and, furthermore, ranges which denote the content and size of the respective bundles of rights and interests. But in such a view, shifts in weighted priority, lexical priority, or exclusionary priority, need not coincide with shifts in the content and size of bundles. This adds another layer of complexity to the idea that moral status admits of degrees and that such degrees can denote differences in the weight of the reason to protect an entity’s bundle, differences in the rights and interests that are considered morally significant, and differences along both dimensions.

In this article, I have examined the idea that moral status admits of degrees. I have argued that we can characterize status properties, which entities can possess to higher or lower degrees, by using the concept of atomic status properties and complex status properties, which are recursively formed from atomic properties via disjunction and conjunction. Moreover, to make sense of the idea that moral status admits of degrees, I have distinguished between

Moreover, differences in degrees of moral status can denote differences in

Subsequently, I have explored some of the complexities that arise when we link degrees of moral status to the weight of reasons to protect bundles and/or the content and size of these bundles. My hope is that this analysis contributes to our understanding of the concept of moral status, the idea that moral status admits of degrees, and the attribution of moral status to nonparadigmatic entities.

On what it means to have moral status, see Warren (1997, 4); Jaworska and Tannenbaum (2013, Introduction); Kamm (2007, 299); Morris (2011, 261); Richardson (2018, 65). Several grounds for moral status have been proposed. For capacities related to self-awareness, see Tooley (1972, 44); McMahan (2002, 45; 242). For paradigmatic human capacities, see DiSilvestro (2010). For capacities related to value and care, see Buss (2012, 352); Jaworska and Tannenbaum (2014); Theunissen (2020, 126–127). For grounds related to agency or autonomy, see Gewirth (1978); Quinn (1984, 49–52); Korsgaard (1996); Sebo (2017); see also Liao (2010). For a multi-criteria account of moral status, see Warren (1997, 148–77).

This does not mean the concept of moral status is without its critics. For example, see Sachs (2011); Horta (2017).

For example, see DeGrazia (2008); Douglas (2013); Kagan (2019); Todorović( 2021).These two ways of construing degrees of moral status are anticipated by Jaworska and Tannenbaum (2013, Sec. 3). Among other things, I aim to give a more thorough articulation of this distinction than Jaworska and Tannenbaum have done. See Sections 3–5 and Fn.26.

On humans with cognitive disabilities, see Jaworska and Tannenbaum (2014); Wasserman et al. (2017). On robots and cyborgs, see Gillett (2006); Jotterand (2010); Mosakas (2021); Gordon and Gunkel (2021). On (cognitively enhanced) animals, see Robert and Baylis (2003); Streiffer (2005); DeGrazia (2007); Palmer (2011); Knutsson and Munthe (2017); Hübner (2018); Wilcox (2020); Arnason (2021). On plants, rivers, and nature, see Midgley (1994); Elliot (1997); Korsgaard (2018, 23–24; 93–94); Kramm (2020); Terrill (2021). For other nonparadigmatic entities, see Cheshire (2014); Søraker (2014); O’Connell (2015); Lavazza and Massimini (2018).

Some accounts say that an entity only has moral status if it possesses the property to a sufficient degree. I discuss such threshold accounts in Section 3.

See Fn.1 for other status properties. Jaworska (2007, 460). For a discussion of rivers and personhood, see Kramm (2020).Elliot (1997, 59). Warren (1997) defends a multi-criterial analysis of moral status that could also attribute moral status nonparadigmatic entities, including those which “are neither living organisms nor sentient beings” (p. 167).

See also Jaworska and Tannenbaum (2013, Section 2). Unless stated otherwise, I will use ‘bundle of rights and/or interests’, ‘bundle of rights and interests’, and ‘bundle’ interchangeably.

See DeGrazia (2008, 186–88).DeGrazia (2008, 192) calls this a ‘sliding-scale model’; Douglas (2013, 478) calls this ‘no threshold’.

Douglas (2013, 477) calls this ‘threshold’. It is also compatible with what DeGrazia (2008, 192) calls the ‘two-tier model’, which attributes full moral status to persons and lower moral status to sentient nonpersons.

For a single-threshold view, see Harman (2003, 183). For multi-threshold views, see McMahan (2007, 93–104); Wasserman et al. (2017, Sec. 2.1); Kagan (2019, esp. 79–111, 215–247, 292–299).

As shown in Figure 1.1, such proportionality can be expressed as a linear function or as a non-linear function.

Unless one means a shift from lacking moral status to having moral status. I leave that issue aside here.

But see Douglas (2013, 479–480) for a variation of this view.The concept of a range property is from Rawls (1971, 444). For a recent discussion, see Miklosi (2022).

See Waldron (2017, 118–19).See, for example, Buchanan (2009, 347; 357; 366–67); Savulescu (2009, 237–38); Wikler (2009, 346); McMahan (2009, 601–2); Wilson (2007).

See also the view described as ‘plateau’ by Douglas (2013, 479–480). Palmer (2011, 277–78).DeGrazia (2008, 186–88) says that degrees of moral status can refer to unequal considerations or unequal interests. This corresponds with my distinction between differences in the weight of reasons or differences in content and size of bundles, though DeGrazia does not seem to distinguish between quantitative and qualitative differences between bundles (see Section 4.2). Subsequently, Jaworska and Tannenbaum (2013, Sec. 3) make a similar though less developed distinction. They say that degrees of moral status can denote differences in strength of the reasons against interference, in the stringency of that reason, in the number of reasons that apply against interference, in the number of presumptions against types of interference, or in a combination of these. Though we can derive from their analysis the two differences that degrees of moral status can denote, Jaworska and Tannenbaum do not offer much conceptual clarity with regards to how these relate. Instead, my analysis brings to the fore that these are actually orthogonal axes along which conceptions of moral status can vary. Moreover, I will argue that we must distinguish between qualitative and quantitative differences in the rights and interests that merit protection. Alternatively, Cohen (2007, 189; 2008, 2–3) suggests that degrees of moral status might correspond with the number of entities that have obligations towards the moral status holder.

This echoes Raz’s idea of exclusionary reasons. See (Raz 1999, 35–48). See Ebert (2018, 86–88). See Jaworska and Tannenbaum (2013, Section 2.1). For discussion, see Kagan (2019, 191–214).Note that quantitative differences between bundles also occur if their elements do not overlap at all. For example, bundle B1 might contain right A but not rights B and C whereas a larger bundle B2 might contain B and C but not A.

Douglas (2013, 476–77). For example, see Regan (1983) For an early multi-criteria account of moral status, see Warren (1997, 148–77).I thank Savriël Dillingh, Nikolas Kirby, Christian Neuhäuser, Eva Schmidt, and Simon Wimmer for their comments on earlier drafts of this article. I am also grateful to the audiences at the Doktorandenworkshop and the Theoretical Philosophy Reading Group at TU Dortmund University for their constructive comments.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.