Refugee resettlement in the United States is administered through a private-public partnership between government agencies and systems of national and local agencies that provide for the initial needs of refugees and place them on a path towards economic self-sufficiency. Generally speaking, there are two primary national models for refugee resettlement: the faith based (or co-sponsoring) model and the secular model. The faith based model of refugee resettlement has received a lot of attention with numerous studies supporting its efficacy in facilitating refugee integration in the U.S. Unfortunately, the more secular model of resettlement, which Nationalities Service Center (NSC) refers to as the community integration model, has received no examination of its methods and success for refugee integration. This article will explore the community integration model of refugee resettlement administered by NSC, a local resettlement agency and affiliate of U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants (USCRI), to provide for the successful resettlement and integration of displaced persons in Philadelphia and engage the local community in resettlement. It is important to note that resettlement, despite the general model that the resettlement agency ascribes to, takes on the flavor of the local community. The local culture and resources available shape a refugee’s experiences just as the approach of their local resettlement agency.

NSC has successfully resettled refugees in Philadelphia since the late 1970s with the mission to prepare and empower immigrants and refugees in the Philadelphia region to transcend challenging circumstances by providing comprehensive client-centered services to build a solid foundation for a self-sustaining and dignified future. As significant actors in refugee resettlement, both Pennsylvania and NSC provide a suitable environment to explore the community integration model. Pennsylvania is the ninth largest resettlement state in the nation, resettling 3,219 refugees in FY 2016, almost four percent of the national total (Radford and Connor 2016).. NSC assisted 17 percent of all refugees resettled in Pennsylvania, which included a total of 549 refugees in FY 2016.

Refugee resettlement policy has evolved in the United States to provide humanitarian assistance to those displaced by war and persecution and since the inception of the U.S. Refugee Assistance Program, it has always involved a unique partnership between the federal government and private agencies. Refugee resettlement has its roots in U.S policy as early as World War II when the War Relief control was created as a liaison between the federal government and private agencies seeking to respond to the crisis overseas (Brown and Scribner 2014). The 1951 UN Convention on the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol outlined the rights of refugees and their hosts. The United States recognized these rights as a signatory (Mayadas and Segal 2003). In 1956, refugee resettlement agencies for the first time received federal money to support the resettlement of 35,000 Hungarian refugees in the U.S. In the years that followed, refugees were resettled on an “ad hoc basis” until the passage of the Refugee Act of 1980 which wrote into U.S law the definition of a refugee as a special immigrant population and created the system of refugee resettlement that provides for their screening, entry, resettlement assistance, and legal status with a path to naturalization.

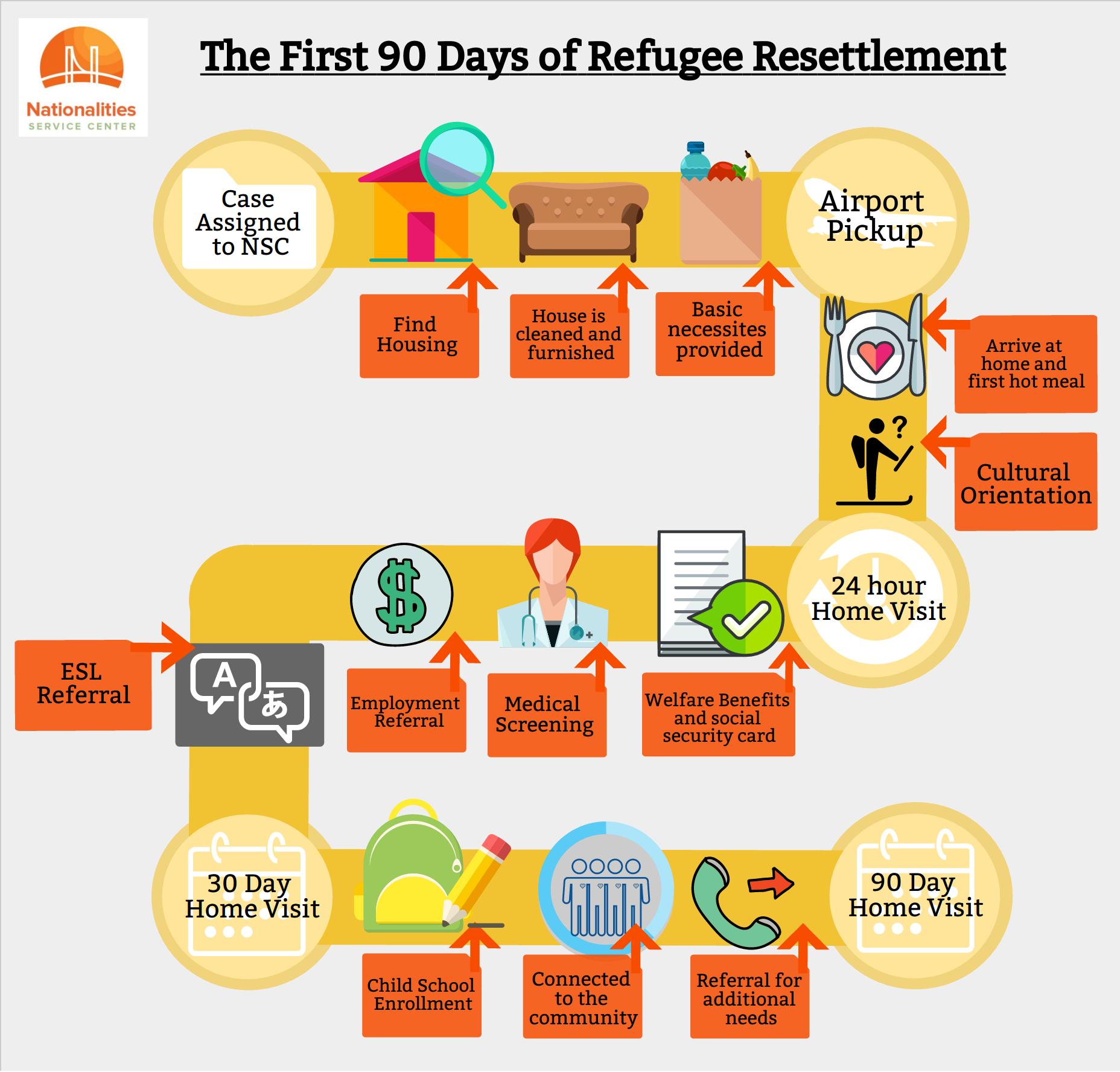

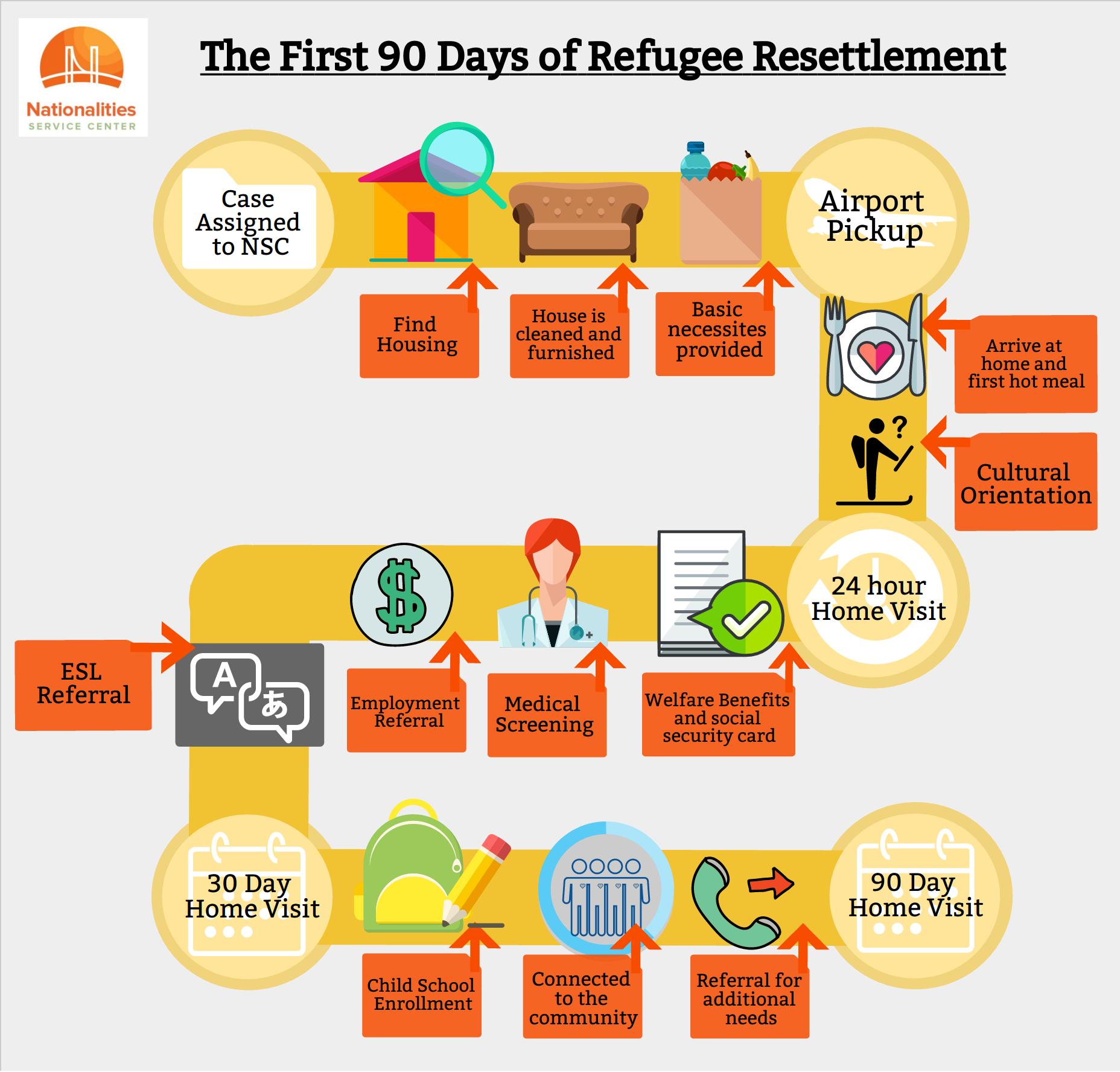

Since the Refugee Act of 1980, the United States has resettled over three million refugees utilizing the relatively unchanged Reception and Placement program. Under the Reception and Placement Program, the Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration (PRM) creates a cooperative agreement with private non-profit agencies, “voluntary agencies or VOLAGs,” which have their own network of local affiliates for resettlement. Each resettlement agency is held to the same standards and must provide the same set of ‘core services’ as outlined in the Cooperative Agreement issued by PRM and outlined in the 1980 Refugee Act (Pub.L. 96-212). These agencies must provide services including preparing housing and transportation, cultural orientations, support for refugees’ basic needs including food, clothing, access to public benefits, and referrals for employment services, health and education for up to 90 days. These core services are summarized in graphic 1. Despite the specific guidelines, resettlement looks very different based on the private partnerships that each resettlement agency has been able to cultivate. Two primary models for refugee resettlement are the faith based co-sponsorship model and the community integration model which both develop unique partnerships to meet resettlement requirements using the strengths and resources available in each community.

Graphic I: Illustration of a Refugee's First 90 Days in the U.S

The most researched public-private partnership in refugee resettlement is the faith-based co-sponsorship model. The focus on this model may be largely due to the national and regional focus on this form of resettlement as well as the long history of faith based service provision in refugee resettlement. Nationally, six out of 10 voluntary agencies assisting in resettlement are religiously affiliated. In the Greater Philadelphia region, three out of four of the local affiliate agencies providing resettlement are connected to regional level VOLAGs affiliated with religious bodies including the U.S Catholic Conference of Bishops (USCCB), Lutheran Immigrant and Refugee Services (LIRS), and the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) (Ives, Sinha and Cnaan 2010).

The faith-based co-sponsorship model primarily utilizes a partnership between a faith-based resettlement organization and a local congregation; however, partnerships with housing providers, medical providers, and schools may also be developed. The partnership with the local congregation provides the resettlement agency with sponsors, who support refugees to meet their basic needs, provide transportation, navigate their new homes, access services, find employment, receive training, build social supports, and improve their English fluency. This model fosters the development of strong connections between the sponsor and the refugee family helping refugees to become connected to their new community. Faith based sponsorship has been found to have many positive outcomes for refugees including higher wages, opportunities for employment advancement, employee benefits and retirement plans, and better English language fluency (Ives, Sinha and Cnaan 2010).

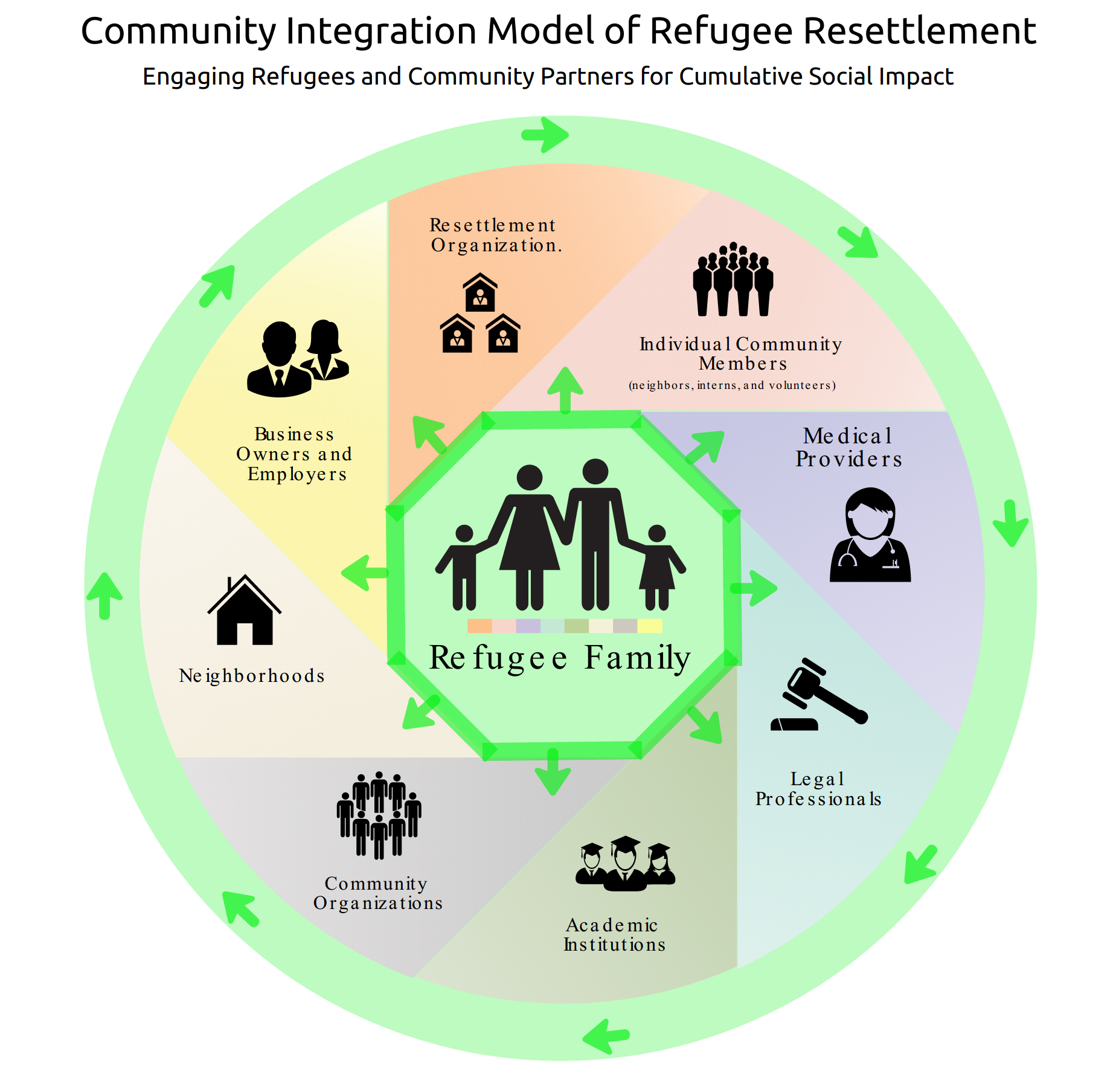

The community integration model has an equally long history in U.S refugee resettlement but has received little research focus. Since 1980, when the public-private partnership was formalized in U.S law, secular agencies have provided resettlement services for newly arriving refugees. The community integration model utilizes a large network of volunteers, interns, and partnerships with local services providers (i.e. medical, housing, and employment providers) to reach the goal of successful integration and engage the local community in refugee resettlement.

Like all refugee resettlement models, the primary goal of the community integration model is to ensure that a refugee is on a path to self-sufficiency and able to navigate systems independently. Refugees must overcome a number of challenges upon arrival in the U.S. In just 90 days, they will enter their new home, receive a cultural orientation, access welfare benefits, have a medical screening, and access any necessary follow-ups; refugee children will begin school; their parents will attend ESL classes and prepare for their first job; the family will build connections with a new community and be expected to be well-on the path to self-sufficiency. In the community integration model, overcoming these early challenges is facilitated by a strengths-based approach to case management that focuses on teaching and guiding refugees as they receive each core service. The refugee family is the main actor in receiving services while the case managers, volunteers, and community members act as resources as the refugee family learns to manage these systems on their own.

Although the primary goal of refugee resettlement is successful integration, NSC has the latent goal of engaging the local community in resettlement. As the refugee family interacts with their new community they work not only with their case manager but with NSC partners including medical professionals, landlords, employers, community leaders, and schools. At the center of each of NSC’s community partnerships is the relationship with a refugee family. These relationships not only provide for the successful integration of the refugee but provide the opportunity for active engagement of key stakeholders. The strength of the relationships built between refugees and their communities helps transform community stakeholders from service providers into supporters and advocates for refugees and refugee resettlement. These stakeholders-turned-advocates have the potential to impact not just the outcomes of refugees in their community but nationally.

To achieve both the latent and manifest goals of refugee resettlement, the community integration model forms a diverse and well-coordinated network of community-based partnerships including NSC’s intern and volunteer program, NSC’s housing strategy, the Philadelphia Refugee Health Collaborative, NSC’s two community gardens, and finally NSC’s new model for permanency, the Refugee Green Card Legal Clinic. Through exploration of each of these five partnerships, the core services of refugee resettlement will be discussed to illustrate how NSC utilizes the community integration model to provide for newly arriving refugees and engage the local community.

Graphic 2: The Community Integration Model of Refugee Resettlement-Community Engagement for Cumulative Social Impact.

The first partnership, NSC utilizes in their model is with volunteers and interns that are placed strategically within the agency enabling NSC to greatly expand both the work on behalf of clients as well as valuable face time with each refugee household. Interns and volunteers receive training and gain hands on experience working with a vulnerable population as they make Philadelphia their new home.

Volunteers to NSC come from many sources, but a significant number of volunteers come from internship opportunities offered through local universities including Rutgers University, Drexel University, University of Pennsylvania, Eastern University, Thomas Jefferson University, and the Philadelphia Center. Interns from these schools come from a variety of disciplines including but not limited to policy, social work, psychology, occupational therapy, and public health and are from both undergraduate and graduate programs. Many interns are directly referred to NSC through established partnerships with local academic institutions. These partnerships are mutually beneficial providing the academic institution with appropriate placements and supervision for students and providing NSC with volunteers who have a keen interest in refugee and immigrant work. While providing direct services, students receive hands on training and mentorship to meet their individual needs and the requirements of their academic program. In addition to direct service, interns are given opportunities to engage in program implementation and evaluation as well as policy practice and advocacy.

NSC has also developed a volunteer program that recruits individuals from a multitude of professions to donate their time and skills including writers, lawyers, social workers, graphic designers, church leaders, and businessman. Most individuals find NSC online or hear about NSC from one of its community partners. All volunteers are interviewed, screened, and then placed in a volunteer setting that engages their interests and unique skillsets. Volunteers may work directly with clients or they may perform support roles such as organizing donations. Volunteers are trained and supervised by a qualified staff member who remain a constant resource for the volunteer.

Volunteers are an integral piece of the community integration model and facilitate the first 90 days of resettlement by helping with housing preparation, cultural and health orientations, and accompaniment services to access benefits and other important appointments. Volunteers in partnership with NSC’s staff provide the main support network for newly arriving refugees. Returning to graphic 1, volunteers act as the yellow path guiding refugees from one service to the next. A refugee will be impacted by an NSC volunteer or intern from pre-arrival in the U.S until the end of their first 90 days. Many refugees will be impacted by NSC’s volunteers far beyond this time for months or years after arrival.

The goal of the volunteer or intern’s work is not just to provide direct services but to teach and empower the refugee to begin to navigate the system independently. The community integration model of refugee resettlement is predicated on the belief that refugees possess the skills and abilities necessary to navigate systems and rebuild their lives and that their greatest need is for information. Christi Kancewik, a long-term volunteer at NSC, describes this role well as one of accompaniment; she finds herself often escorting clients to various offices for public benefits, school enrollment, or other needs and describes her presence as a positive energy as she helps newly arrived refugees learn how to navigate transportation (a scary experience for many) and new systems to meet their needs. As, Christi so well describes, the role of the volunteer or intern is to create positive learning experiences to promote self-sufficiency (2017).

In NSC’s fiscal year running from June 2016 to May 2017, NSC hosted 309 volunteers and interns who worked in service to newly arrived refugees contributing 17,847 hours of service. During this same period, 587 refugees were resettled resulting in 30.4 hours of volunteer service per resettled refugee. To cover the hours invested in NSC’s clients by volunteers, NSC would have to hire nine new full time staff. These hours have an incredible impact on the resources available to resettled refugees and enable NSC to provide comprehensive services to each refugee family.

The benefits of volunteer work are far greater than just service hours; as each volunteer has the potential to become part of a network of advocates for refugee resettlement. Each volunteer meets with and builds relationships with the refugee families they work with and often become deeply passionate about refugee resettlement. Although the social impact of a large volunteer network is hard to quantify, NSC has already seen the benefits of engaging volunteers in their work. Responding to the interest of interns and volunteers in U.S immigration, NSC has begun piloting a Social Media Ambassadors Program that keeps volunteers aware of important immigration and refugee news and challenges them to engage others in discussion on important developments in U.S immigration. Although this program is in its infancy we hope that it will spread the reach of NSC and the support for refugee resettlement. Beyond just this project, volunteers have stepped in to help NSC advocate for refugees online, by mail, at events like World Refugee Day, and in partnership with NSC on projects like the “We are Neighbors” video project. The level of support and community outreach NSC and its clients receive from the engagement of its volunteers is immeasurable and invaluable.

The average length of stay in a refugee camp is 17 years (United Nations High Commissions for Refugees 2017). This protracted time in a refugee camp does not provide refugees with a sense of permanency but creates dependence on the international community. To help refugees transition from dependency to inter-community independence and integration, NSC seeks to place refugees from similar backgrounds in neighborhoods close together and within proximity to the resources necessary to establish normalcy. NSC does this by working with community leaders and planners to identify neighborhoods within Philadelphia that will provide refugees with the opportunity to meet their new neighbors and where they will have access to needed services including ethnic markets and grocery stores, laundromats, day care centers, places for recreation and worship, public transportation routes and potential employment opportunities within reasonable commuting distance. NSC partners with landlords in these neighborhoods to ensure that upon arrival, a refugee is able to move directly into their own home.

The housing process facilitates two main stages of refugee integration in the first 90 days and creates a foundation for each other stage. First and foremost, housing provides a stable home for the refugee to rebuild their lives. Within days of arrival, NSC facilitates a meeting with the landlord and a lease is signed. The lease is in the name of the refugee and emphasis is placed on working with them to establish a sense of ownership and connection to their first home in the U.S. During this time case managers educate refugees on how to maintain and care for a home. Almost as important as this sense of ownership and security, is the physical address of the refugee’s home. A stable address is the first necessary step in getting an ID, applying for public benefits, finding schooling, or getting a job.

Additionally, a home provides the first introduction to community and social support for a newly arrived refugee. Refugees, as new neighbors, work to support each other in exploring and engaging with their new community. For a newly arrived refugee, a simple lesson in the difference between a quarter and a bus token is highly valuable. These lessons are shared when refugees are placed in housing in close proximity to each other. NSC works to develop refugee community leaders in refugee neighborhoods. Refugee community leaders are invaluable as they develop intra-community networks that help spread information to newly arriving refugees and build support networks to help refugees meet their basic needs. Together, partnerships with landlords and refugee community leaders provide for the successful housing and integration of refugees in new communities.

The impact of this strategy is difficult to measure but we see evidence of how this has successfully worked when looking at the emerging role of formal non-profits such as the Bhutanese Association of Philadelphia (BAOP) and the online network of the Burmese American Community of Philadelphia. BAOP actively works to support neighborhood cleanup activities and engages refugees in working alongside their new neighbors. The Burmese American Community of Philadelphia exists primarily as a social media group aimed at providing information and linking refugees from Burma to resources in Philadelphia. In addition to these formal non-profits, NSC also works with informal community groups who not only share resources with each other but are willing to support NSC at local events and share their stories. These groups act not just as facilitators for community integration but as advocates for refugees in their communities. As groups like the BAOP work within their community they are able to improve refugee integration and build strong relationships with their neighbors.

Refugees arrive in the United States with medical needs or have not been afforded the opportunity to access preventive care. To meet a refugee’s health needs requires collaborative support from multiple stakeholders. Many arriving refugees have not been able to access preventive health care while living as a refugee and many have untreated war-related injuries. While a refugee's first needs upon arrival are housing and basic necessities, a health screening must quickly follow to address any underlying health concerns and to clear a refugee for work. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that all refugees receive an initial domestic health screening within the first 30 days following arrival. Delays to a health screening often cause other delays, including delayed entry into school, employment, or social security benefits, and negatively affect overall integration and resettlement success.

For decades, health screenings were set up by the resettlement agency by referring newly arriving refugees to physicians who accepted Medicaid at a local health clinic. This ad-hoc system of referrals fell far short of the CDC’s goal of a 30 day health screening. Refugees often waited up to 80 to 90 days for initial screening appointments. For refugees with complicated health conditions, waiting for this first screening meant long delays in addressing their health needs. Resettlement agencies and private healthcare providers recognized the need for culturally competent, high quality screenings within a short wait time.

In 2007, NSC and the Department of Family and Community Medicine at Thomas Jefferson University piloted a new refugee health clinic model, creating a symbiotic partnership between a resettlement agency and a medical provider. Following initial pilot testing and demonstrable success in terms of performance metrics, refugee community satisfaction, and provider engagement, this partnership model was replicated at numerous medical sites and the other two refugee resettlement agencies serving Philadelphia. Together, this network was formalized as the Philadelphia Refugee Health Collaborative (PRHC) in 2010, which established initial goals of equity in health care access and quality of care for all refugees resettled in Philadelphia. In an effort to expand PRHC capacity, NSC approached nearby clinics likely to have the capacity, staffing, and desire to work with refugee patients. While PRHC has seen new partners join and founding partners transition out of the collaboration, it has maintained great partnerships that allow for increased capacity, culturally competent care, and a sustainable system for refugee clients in Philadelphia.

Today the PRHC consists of twelve health clinics providing initial screening and ongoing refugee health care. The PRHC model relies on clinical champions who work closely with Philadelphia-based resettlement agencies, and have recognized the value of a common mission, formal and informal communication, and mutual support to achieving shared goals and improved resettlement success. We have learned the importance of combining and sharing resources and training. This has enabled innovative non-competitive relationships across partners and multiple shared research projects including several funded by the CDC. For example, NSC and partners from the Jefferson Center for Refugee Health recently participated in a study examining the impacts of the joint International Organization on Migration-CDC project to increase overseas immunizations for refugees prior to arrival and the cost savings realized on the U.S. side.

Since 2007, when PRHC was piloted, the average wait for a refugee health screening has decreased from between 80 to 90 days to 22 days. With PRHC, resettlement agencies in Philadelphia not only meet but exceed PRM’s recommendation of 30 days. The ability to meet the evolving healthcare needs of refugees with different models of care has the potential to improve healthcare outcomes for all refugees in the Unites States. This collaborative approach is community-focused across agencies and institutions and non-competitive, which has led to faster screening appointments, improved health outcomes, and established medical homes. While there are challenges to overcome, this model has demonstrated success and scalability and offers opportunities for replication in other communities.

The PHRC has had great success in improving refugee health outcomes and has the added benefit of engaging key stakeholders in refugee resettlement. PHRC works with prestigious institutions that allow refugees to directly interact with medical professionals that can have an important impact on refugee health nationally. The refugee provides medical students and providers with valuable experience treating health conditions that they may not otherwise encounter, while also ensuring the refugee receives quality care. This partnership has already formed several research projects that can improve refugee healthcare and service provision. This collaborative approach to refugee healthcare is remarkable in both its ability to serve refugees and in its potential for lasting impact on refugee healthcare.

One of the final steps during the first 90 days is connecting the refugee to a community. Though this step is second to last, the process of connecting to a community is ongoing and lasts far beyond the first 90 days. To successfully integrate and become self-sufficient it is important that a refugee connect to their new home and build a network of social supports. A home to call their own is the critical first step in integration, but given the barriers created by language and cultural divides, refugees can often struggle to meet and work with their new neighbors. NSC searched for a way to create links between refugees and their new neighbors and found inspiration in a conversation with a refugee elder. When asked if she felt a connection to her new community, she stated that if she could place her fingers in the dirt and have access to land to grow food for her working family, then she would be truly happy. In this elder’s story, NSC saw the potential of a community garden to grow community integration.

Kaflay, reclaiming a connection to the land through one of NSC's community gardens. (Photo Credit: Jenn Hall)

NSC launched its first community garden in 2011. Now, in partnership with Pennsylvania Horticultural Society (PHS), Neighborhood Gardens Trust, the City’s Parks and Recreation, Public Property and Water Departments, Church of the Redeemer Baptist, the East Park Revitalization Association (EPRA) and countless volunteer groups who commit to support monthly workdays, NSC operates two community gardens with over 600 raised beds. The express goals of the gardens are to offset food budgets by helping refugees grow their own food (including specialty crops such as African eggplant, bitter melon, chin baung ywet, and bangkok hot peppers), put down roots in their new community, work alongside their new neighbors, and gain new skills as they explore growing food in an urban area. Now in the sixth growing season, refugees are recognized and valued for their contributions to food diversity in our region, sought out for their skills in seed saving, and perceived not as foreigners but as neighbors.

Of the 600 raised beds offered at two community gardens, 250 are cultivated by entrepreneurial growers. These growers are participating in a farmer training program and are refugees as well as residents from the Strawberry Mansion neighborhood. The growers harvest specialty crops that are donated to NSC to distribute to newly arrived refugees and sell at local farmers markets. NSC is currently in an effort to expand sales to create a meal package including grain (rice or couscous), produce, spices and a protein (chickpeas or lentils). The remaining 350 raised beds are assigned to refugees and their new neighbors who are able to grow their own chemical-free produce from the month of April to early November (weather permitting). We estimate that the amount of produce harvested from each raised bed is valued at more than $600. Given this, 350 families are able to offset their food budgets with more than $6,000 in fresh, chemical free produce.

The Community Garden is a truly collaborative project that engages multiple levels of the community including new refugee residents, neighborhood residents, and numerous local organizations. In this partnership, refugees are able to act as the teachers, working with local residents and community organizations to grow crops from the refugee’s country. In this role refugees are able to show one of the many unique skills that they bring to their community and build relationships with their new neighbors. With over one hundred families currently working in the garden, there is great potential for relationships to build across communities; leading to improved community integration for the refugee and a better understanding of refugee resettlement across Philadelphia.

The first 90 days of resettlement prepares refugees for permanency by providing for their immediate needs upon arrival. When a refugee arrives in the US, they arrive on a path to citizenship and are fully authorized to work. To continue on the path to citizenship, a refugee, after one year of residency, can adjust their status to receive their green card. Then, after five years in the U.S., a refugee is eligible to apply to become a U.S citizen. For many refugees, navigating the path to permanency is confusing, time consuming, and expensive requiring photographs, medical screenings, inoculations, copious amounts of paperwork, and bureaucratic delays. After the rise in anti-immigrant sentiment and the changes to refugee resettlement following the outcome of the 2016 election, many refugees have become fearful of their status in the U.S. Providing a path to permanency not only helps refugees feel more secure but moves them closer to achieving citizenship, a distinction and an honor that refugees highly value.

With feedback from refugee community members that the heightened anti-immigrant sentiment had left them feeling vulnerable, NSC worked to identify new partners to support refugees in seeking the pathway to permanency and aiding them in feeling more secure here in the U.S. NSC partnered with students from the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Law to create a legal clinic model for adjustment of status. The legal clinic model we developed uses a combination of community outreach, individual case-by-case preparation and direct legal services.

NSC provided community outreach by partnering with NSC’s refugee community leaders to educate refugee communities on the adjustment of status process and NSC’s legal clinic. Each refugee who sought assistance met with an NSC intern to discuss their individual case, the documents they needed and how to obtain them. These meetings also enabled NSC to take note of any refugee households that needed additional assistance with the adjustment of status process. Once a refugee had reached one year of residency and prepared their needed documents they attended a legal clinic date where their application was processed by a law students from the University of Pennsylvania.

At the end of the three clinics offered during the Spring semester, 84 refugees submitted their applications for a green card. In just seven months, with the support of volunteers from Philadelphia’s legal community, more than 250 refugees have been assisted in completing and filing their applications for their green cards, representing a one hundred percent increase in the number of applications filed in 2016. The unique university partnership we created will continue during the upcoming school year and has expanded to include clinics at the Blank Rome law firm during the summer months where more than one hundred refugees will be assisted.

Partnerships with these law schools and law firms not only provide free legal aid for refugees as they apply for their green card but provide an opportunity for lawyers and law students to become more familiar with the needs of refugees and their growing legal concerns. The relationships formed now with law schools and law professionals can have an enormous impact on the future of immigrant access to services and the protection of immigrant rights. The impact of community partnerships with legal professionals has already been witnessed in the overwhelming legal response to the travel ban. Following the outcome of the 2016 election, Philadelphia’s legal community has mobilized and hosted a series of information sessions under the name Take Action Philly. The result for NSC has been a strengthened partnership with pro bono coordinators at area law firms who have extended invitations to host additional adjustment of status clinics or are working to create opportunities to expand pro bono work in support of immigrants and refugees. More than this, these budding partnerships have sent a much needed message to once stateless refugees that they are wanted and accepted -- even in Center City corporate law firms.

Integration of refugees in the community is a complex and multilayered process that involves a refugee finding comfortable housing, employment, social connections, language and cultural acquisition, safety, and stability. There is no approach to evaluating refugee resettlement that adequately captures the multitude of challenges and transitions in refugee integration. NSC is currently working to create an evaluation tool that we are calling the Self-Sufficiency Indicator Tool or SSIT. The SSIT measures not just employment but also a refugee’s connection to community resources, ability to access health care and other services independently, knowledge of basic budgeting and financial management. The tool is currently being tested and validated and data is not yet available. NSC looks forward to evaluating the community integration model with this new measure.

The community integration model not only provides for the successful integration for refugees but has important social and political implications in the face of changing attitudes on immigration and refugee resettlement. The community integration model not only creates a network of new support for newly arriving refugees but expands the resettlement agencies’ and the refugees’ contact with surrounding communities. NSC believes that exposure to refugees and refugee resettlement is the greatest way to combat misunderstanding and mistrust of refugees in Philadelphia and across the U.S. The more networks NSC and its clients engage in, the more advocates NSC can develop for refugees.

In each of the five partnerships discussed, individual community members, organizations, and business were engaged with refugees. Working with colleges and universities enables NSC to provide interested students with direct contact with refugee families. When a student works with a refugee they learn how valuable refugees are and the amazing resilience refugees possess. Students take this lesson back to their schools, homes, and communities and spread support for refugees.

In addition to students and volunteers, NSC engages landlords and community leaders introducing them to refugees and allowing them to see the contributions refugees can make in a community. Community leaders are best positioned to challenge the belief that refugees drain public resources and do not contribute to the community. Their first-hand experiences with refugees opens the door to new communities for refugees and can begin to change the mindset of the neighbors of refugees in Philadelphia.

Working with renowned institutions like Thomas Jefferson University and the University of Pennsylvania provides invaluable support for our refugees and enables NSC to not only access highly needed medical and legal help but connects NSC to a larger network of social change. Doctors, students and pro bono lawyers who meet our clients are able to share their experiences with their colleagues and build a greater network of support with the capacity to enact real change.

Through its partnerships, refugees resettled by NSC interact with more than 500 individuals including volunteers, interns, landlords, and community members and more than 30 academic institutions and organizations. At the center of each one of these interactions is the refugee family. Centering these partnerships on the relationships between the refugee and their community has an incredible potential to combat the misunderstandings and fear surrounding refugees and refugee resettlement. As these partnerships grow and expand they build networks of advocacy that can have a cumulative social impact far greater than any network NSC could develop alone. The greatest strength of the community integration model is the breadth of support it generates. The more people refugees connect with, the greater the social impact. In a time of uncertainty in immigration policy and refugee resettlement, these connections are not only highly valuable but also necessary for survival.

Though faith-based models of refugee resettlement have had great success, it is important to explore new partnerships in refugee resettlement and their impact on refugee integration. NSC’s community integration model is just one of many examples of public and private partnerships in the U.S., but they provide a well-rounded picture of the types of partnerships a resettlement agency can cultivate. Within its model, NSC has created a strong volunteer and intern network, connected neighbors through a community garden, formed new relationships with refugee community leaders and landlords, and created two new clinic models for refugee health care and permanency. The diversity of these partnerships is not only a strength for successful resettlement but for the ongoing political and social future of resettlement in the United States.

Works Cited

Brown, A., and T. Scribner. 2014. Unfulfilled promises, future possibilities: The refugee resettlement system in the united states. Journal on Migration and Human Security 2 (2): 101-20.

Ives, Nicole, Jill Witmer Sinha, Ram Cnaan. 2010. Who is welcoming the stranger? Exploring faith based service provision to refugees in Philadelphia. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work 29 (1): 71-89.

Kancewick, Christi. Volunteer profile - Christi Kancewick. 2017 [cited April, 20th 2017]. Available from Link (accessed March, 20th 2017).

Mayadas, Nazneen, and Uma Segal. 2000. Chapter 6: Refugees in the 1990s: A U.S perspective. In Social work practice with immigrants and refugees., ed. P. R. Bagopal, 198-223. New York: Columbia University Press.

Radford, Jynnah, and Phillip Connor. 2016. Just 10 states resettled more than half of recent refugees to U.S. Pew Research Center, Link (accessed March, 20th 2017).

The Refugee Act of 1980. Pub.L. 96-212. (1980) United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2017. "What We Do." Accessed July 12th. Link

Author Bios

Naomi Burrows is a Master of Social Work from Rutgers University who completed her second-year internship with Nationalities Service Center’s Refugee Resettlement Program. As an immigrant from England, Naomi has always felt a close personal connection to immigration in the United States. She focused her master’s level education on human trafficking and refugee resettlement policy, and has a keen interest in evaluating policy and its impact on micro-level practice.

Juliane Ramic joined the Nationalities Service Center team in 2004. As the Senior Director for Refugee and Community Integration, she oversees the agency’s services to refugees, asylees, and victims of human trafficking including services to individuals and families, group work, and ethnic community building. Juliane has designed and implemented programs aiming to ensure newly arriving refugees are able to achieve self-sufficiency and economic independence. Prior to joining NSC, she worked at Immigration & Refugee Services of America (IRSA, now the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants) where she monitored federal contracts from three federal agencies and provided technical assistance to a network of 26 agencies. Juliane’s extensive work with refugees includes work with local communities, national organizations, and refugee camps in east Africa. She holds an MSW from The Brown School at Washington University in St. Louis.